By Bethan Jenkins, January 2007

Although Duck's work as a farm thresher probably makes him a serious contender for the title of "the hard man of eighteenth-century poetry", the purpose of this paper is not to postulate that Stephen Duck, the 'Thresher Poet', was some kind of eighteenth century poet ninja; nor am I going to be speaking specifically about swords or ploughing; or even say that he was carefully skilled and schooled in the principles of The Art of Defence as we have heard it described in the previous papers this afternoon. However, certain lines of Duck's most famous poem, The Thresher's Labour,those treating the business of threshing, seem to me to be, rather than simply decorative metaphor, a practical description drawn from life of the dual function of the flail or threshall as agricultural implement and weapon. Anthony Day writes to accompany this engraving of the threshing room:

It was not an unskilled job to use those flails to full effect, but then farmyards were full of offensive weapons if you regarded them as such.

The lines I wish principally to discuss are lines 27-41 (here quoted from the 1730 version of the poem):

So dry the Corn was carried from the Field,

So easily 'twill Thresh, so well 'twill Yield;

Sure large Day's Work I well may hope for now;

Come, strip, and try, let's see what you can do.

Divested of our Cloaths, with Flail in Hand,

At a just Distance, Front to Front we stand;

At first the Threshall's gently swung, to prove,

Whether with just Exactness it will move:

That once secure, more quick we whirl them round,

From the strong Planks our Crab-Tree Staves rebound,

And echoing Barns return the rattling Sound.

Now in the Air our knotty Weapons fly;

And now with equal Force descend from high:

Down one, one up, so well they keep the Time,

The Cyclops Hammers could not truer chime...

Duck's use of classicising metaphor, an example of which occurs at the end of this extract, has been dealt with elsewhere, and has been seen to a greater or lesser degree as Duck's way of making his poetry fit in with the Augustan poetic standard of his social superiors, "the anxious classical reference" to use Raymond Williams' phrase. The extended martial metaphor in this passage is not so jarring as the references to Sisyphus, Ætna, Cyclops and so forth, all of which are italicised in the printed text in order to make them unmissable. The ease with which the language of the Art of Defence is assimilated into the text so that it is barely noticeable suggest that the knowledge of the use of the flail as a weapon was a commonplace one at the time.

Anyone who has difficulty conceiving of the flail as anything other than a tool for threshing corn might usefully bear in mind the Morgenstern or Morning Star, essentially a large metal battlefield version of the threshall:

Obviously a very nasty weapon even to the untrained eye! But it does work on the same basis as a corn flail. A description of the parts of a flail appears in Randle Holme's Academy of Arms and Armoury of the seventeenth century:

The parts of a Flail or Threshal.

The Hand Staff, that as the Thresher holds it by.

The Swiple, that part as striketh out the Corn.

The Cap-lings, the strong double Leathers made fast to the top of the Hand-staff, and the top of the Swiple.

The Middle-Band, that Leather Thong, or Fish Skin as tyeth them together.

A Threshall or Flail, some corruptly a Frail, when all compleated together.

In this picture of a modern-built flail, the middle-band and the cap-lings are made of metal chain, as was seen on the morning star, and in the nunchaks in innumerable oriental martial arts' films. A leather middle band would have been less likely to get tangled around itself and stuck than metal chain. In this photo of a flail from an exhibition in Peterborough Museum about a later Peasant Poet, John Clare, the cap-lings are metal, whilst the middle band is of leather, a far more practical farming solution than those made for Live Action Role Players and so forth.

The Hand Staffs of these farm threshalls would be roughly four or five feet long, the Swiple another three to four feet; a commoner's battlefield weapon (as opposed to the Morning Star) could be anything up to eight feet long in the Hand Staff.

No manuals exist for the use of the threshall in combat; Anciant Maister Terry Brown is of the opinion that it may be treated as essentially a Staff with a swingle on the end, and manuals on the staff treated accordingly. George Silver says of the staff that the

...man that rightly understands it, may bid defiance and laugh at any other weapon...

Silver also comments on the staff's recommended military length:

...you shall stand upright, holding the staff upright close to your body with your left hand, reaching with your right hand your staffe as high as you can, and then allow to that length a space to set both your hands when you come to fight, wherein you may conveniently strike, thrust and ward, and that is your just length according to your stature. And this note, that those lengths will commonly fall out to be eight or nine foot long...

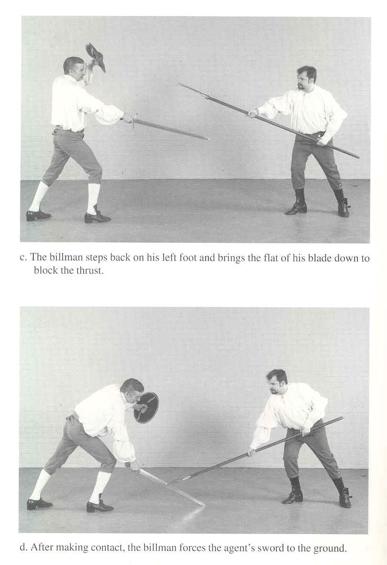

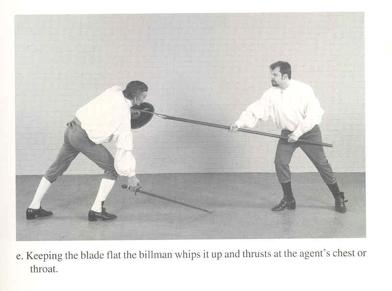

A staff, a long weapon, can 'wide-space' a shorter weapon; because of the reach of the staff, it means that the user of the shorter weapon cannot, by taking up a guard, adequately cover all the places that the staff man may attack him. This can be seen in these photographs from Anciant Maister Brown's book showing the martial use of another agricultural instrument, the billhook, against a sword and buckler man.

To quote Silver once more:

...if these weapons [such as the staff &c.] be of their perfect lengths then can the long staffe, the Morris Pike, or anie other longer weapon ly no where in true space, but shall be still within compasse of the crosse and uncrosse, whereby he may safely pass home to the place, where he may strike or thrust him that hath the long weapon, in the head, face, or body at his pleasure.

Now for the vantage of the short Staffe against the Sword & Buckler, Sword and Target, Two Hand Sword, Single Sword, Sword and Dagger, or Rapier and Poiniard, there is no great question to be made in anie of these weapons: whensoever anie blow or thrust shall be strongly made with the staffe, they are ever in a false place, in the carriage of the wards...

(Point out that Silver declares the staff superior to the Bill "by reason of the nimbleness and length", but this is just a convenient set of pictures to use)

Though fighting with such agricultural instruments was not codified in manuals in the same way as fighting with other, more 'upper-class' weapons intended for combative functions alone, most able-bodied men would know how to fight with them, and the same principles of the Art would apply. William Hogarth put a fighter with a flail in his engraving Chairing the Member

If we go closer in:

Notice that the thresher is standing roughly in the correct fighting stance, giving himself a broad base and firm grounding with his feet, holding his flail in a position to deliver a right oblique blow with his flail. His distance is such that he will quite easily connect with his assailant, but his assailant, wielding a much shorter cudgel, is unlikely to deliver a connecting blow.

Violence was far more of a fact of everyday life then than now, and in an age of frequent wars, the ability to fight would have been passed on unofficially through the populace at large. Anciant Maister Brown defines the Four Grounds of the Art of Defence as

- Judgement

- Distance

- Time

- Place

He explains:

Judgement means the ability to maintain the optimum distance between yourself and your adversary. The optimum Distance is to be out of striking range of your opponent but close enough to take advantage of any openings that occur. Time is that moment when you may safely attack your opponent without him being able to immediately reciprocate. Place refers to an opening in his defence through which you may deliver your attack. Through Judgement you keep your Distance, through Distance you get your Time, through Time you safely win the Place in which to strike your opponent.

It is not too great a stretch of the imagination to apply these Four Grounds to the farm work in the threshing barn itself - a thresher would have to judge his distance so as not to hit another with his flail, or be hit himself; and folklore studies of flailing routinely speak of the importance of judgement and strict time in flailing, keeping a rhythm on the threshing room floor.

The rhythmic singing of the flails was of great importance for the threshing. They could not sing while the threshing was going on, for the work was too hard, and the room was filled with dust. In some places, it is noted that the first blows with the flail fixed the speed, and afterwards they were threshing in the same rhythm.

To turn, then, to the poem itself. The academic community has recently begun to read Duck's poetry as poetry, rather than as a curiosity or an historical testament. I don't intend to go back to diminishing Duck's work to the status of mere eyewitness account; but the use of the martial metaphor in these lines is too detailed merely to be accidental. If we look at the text again, we can see how each stage of the threshing can also be read as the stages of a fight. "Come, strip, and try, let's see what you can do" is phrased as a direct challenge, and the threshers strip clothes as a stage gladiator or a pugilist would have done in preparation for the fight. Duck uses the phrase "to try" again at line 113 when the threshers exchange their flails for scythes:

And now the Field design'd our Strength to try

Appears, and meets at last our longing Eye...

calling to mind stage-gladiatorial contests, or the tests of strength and martial skill such as in the English Olimpicks in the Cotswolds. Of course, the only prize Duck's combatants win is "only t'excel the rest in Toil and Pains". Duck has his threshers standing "at just Distance, Front to Front"; Distance, as we have seen, being the second of the four Grounds of martial art. Here the threshers are as though squaring up for confrontation; before beginning a fight, two opponents will square up at such a distance that the opponent would have to use a slower time (which we have hopefully heard about earlier!) to perform an attack; that is, he must put in his foot in order to reach, whilst also being out of reach of his opponent. This would be the "just Distance" of which Duck speaks. The threshers then move on to a few test swings, "to prove Whether with just Exactness it will move". Once it is proven that the combatant threshers are at the just Distance, and swinging with just Exactness, then the pace and rhythm pick up, and Duck openly refers to the threshalls as "knotty Weapons". It is interesting to note in passing that he calls the threshalls "Crab-Tree Staves" - the threshall as staff, as has been noted before, and made from crab-apple wood. Crab-apple is an extremely dense wood, very heavy, and tends not to splinter, usually used for making wooden mallets - Duck goes on to compare the sound of the flail with the sound of the Cyclops' hammers. An ideal wood for lending weight for the threshing of corn, and indeed the threshing of pates.

Duck returns to his martial metaphor at points throughout the poem. Intriguingly, he writes that

The Threshall yields but to the Master's Curse.

A mob of peasants armed with the weaponry of the farmyard would have been more than a match for Duck's stubble-grubbing master and his curses. Yet the threshers in Duck's poem stand for the Master's rebukes like a line of naughty schoolboys caught in the act:

Now in our Hand we wish our noisy tools,

To drown the hated Names of Rogues and Fools;

But wanting those, we just like School-boys look,

When the Master views the blotted Book.

The tools are wished for, not to beat the master, but for their noise to drown out the master's accusations. Moira Ferguson writes of The Thresher's Labour that "an absence of complaint further enhance[s] the work" - but the martial metaphors in the poem thread a current of threat throughout it. Weapons, cutting, Blows, even Haymakers (both a farming tool and a kind of blow in pugilism), all are the language of the farm and the language of the battlefield. The flail itself has a history of martial use in poetry, and always as a working-class weapon. "A Flail" is the answer to riddle 52 of the Anglo-Saxon Exeter Book;

I saw the captives carried into the barn,

Under the hall's roof: a hard pair,

They have been taken and tightly bound

In a firm lashing. Leaning on the second

Was a dark Welsh girl, who directed them

Cramped into their fetters, on their course together.

the fifteenth-century burlesque The Turnament at Tottenham outlines a labouring-class parody of courtly jousting contests for the hand of a fair maiden, with the participants wielding flails instead of lances; whilst the sixteenth-century ballad The Protestant Flayl makes the martial and the revolutionary potential of the threshall even more apparent:

Now listen a while and I'll tell you a tale

Of a New Device of a Protestant Flayl,

With a thump, thump, thump, a thump

thump, a thump, thump

This flayl it was made of the finest wood

Well lined with lead, and notable good

For splitting of Bones and shedding of Blood

Of all that withstood

With a thump, thump, thump, a thump,

thump, a thump, thump.

This Flayl was invented to thrash the Brain

And leave behind not the weight of a grain

With a thump, thump, thump, a thump

thump, a thump, thump

At the handle-end there hung a weight

That carrie within unavoidable Fate,

To take the Monarch a rap in the pate,

And govern the State,

With a thump, thump, thump, a thump

Randle Holme quotes the flail in a Biblical context regarding the last Judgment, where the Flail shall not only make a separation between the Chaff and the Corn, but is said to be the Judgment and Punishment of all Wicked persons.

Of course, Duck's action is to fight his master using words rather than the considerable martial might of a group of threshers - the reasons for which are not within the scope of this paper. But the subtle nexus of martial allusions in The Thresher's Labour contrast sharply with his "anxious classical references" - they are so far from being anxious that they are barely noticed, suggesting that the martial arts were something far more commonplace and unconscious to Duck than writing of Sisyphus and the Cyclops.

Brown, Terry. English Martial Arts: Anglo-Saxon Books, 1997.

Christmas, William J., Bridget Keegan, and Tim Burke. Eighteenth-Century English Labouring-Class Poets 1700-1800. London: Pickering & Chatto, 2003.

Williams, Raymond. The Country and the City. London: Chatto & Windus, 1973.

Anthony Day, Farming in the Fens: A Portrait in Old Photographs and Prints (S.B. Publications, 1995)

William J. Christmas, Bridget Keegan, and Tim Burke, Eighteenth-Century English Labouring-Class Poets 1700-1800 (London: Pickering & Chatto, 2003) Vol. 1, p. 140.

Raymond Williams, The Country and the City (London: Chatto & Windus, 1973).

Quoted in Terry Brown, English Martial Arts (Anglo-Saxon Books, 1997) p. 67.

Sandklef, Albert, Singing Flails: A Study in Threshing-floor Constructions, Flail-threshing traditions, and the Magic Guarding of the House. (F. F. Communications, X, Vol. LVI)

Old English Riddles from the Exeter Book, Michael Alexander (Poetica 11; Anvil press poetry, 1980) p. 44

"The Protestant Flayl", Ballads and Music of the Early Seventeenth Century Vol. 1, ed. David Stell (Stuart Press, 1994)